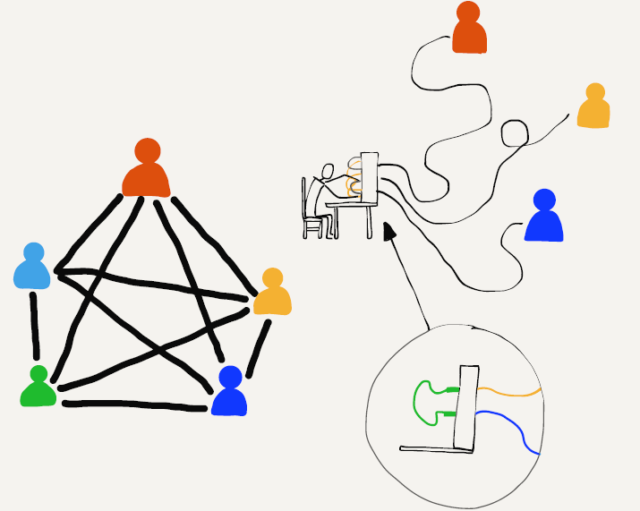

Imagine a group of five people in a room sitting in a circle. As long as they are courteous and don’t have more than one conversation at the same time, it’s quite natural for any person to talk to any other person in the room. They just need to be able to hear each other and coordinate how to use the shared space in the room.

But what if we put these people in different rooms so they can no longer see or hear each other? How could pairs of people communicate with each other then? One way might be to run a wire between each pair of people with a microphone on one end and a speaker on the other end. Now everyone could still hear all the conversations. They would still need to be courteous to make sure that there was only one conversation going on at the same time.

Each person would need four speakers (one for each of the other people) and enough pieces of wire to connect all the microphones and speakers. This is a problem with five people and it gets far worse when there are hundreds or thousands of people.

Using wires, microphones, and speakers is how early telephone systems from the 1900s allowed people to make phone calls. Because they could not have separate wires between every pair of telephones, these systems did not allow all pairs of people to be connected at the same time. Each person had a single connection to a human “operator”. The operator would connect two wires together to allow a pair of people to talk, and then disconnect them when the conversation was finished.

The first local telephone systems worked well when a customer’s home or business was close to the operator’s building and a wire could be strung directly from the operator’s building to the person’s home.

But what if thousands people who are hundreds of kilometers apart need to be able to communicate? We can’t run 100 kilometer wires from each home to a single central office. What the telephone companies did instead was to have many central offices and run a few wires between the central offices, then share connections between central offices. For long distances, a

connection might run through a number of central offices. Before the advent of fiber optic, long-distance telephone calls were carried between cities on poles with lots of separate wires. The number of wires on the poles represented the number of possible simultaneous long-distance phone calls that could use those wires.

Since the cost of the wires went up as the length of the wire increased, these longer connections between offices were quite expensive to install and maintain, and they were scarce. So in the early days of telephones, local calls were generally quite inexpensive. But long-distance calls were more expensive and they were charged by the minute. This made sense because each minute you talked on a long-distance call, your use of the long-distance wires meant no one else could use them. The telephone companies wanted you to keep your calls short so their long-distance lines would be available for other customers. When telephone companies started using fiber optic, more advanced techniques were used to carry many simultaneous long distance conversations on a single fiber. When you look at an old photo and see lots of wires on a single pole, it generally means they were telephone wires and not used to carry electricity.