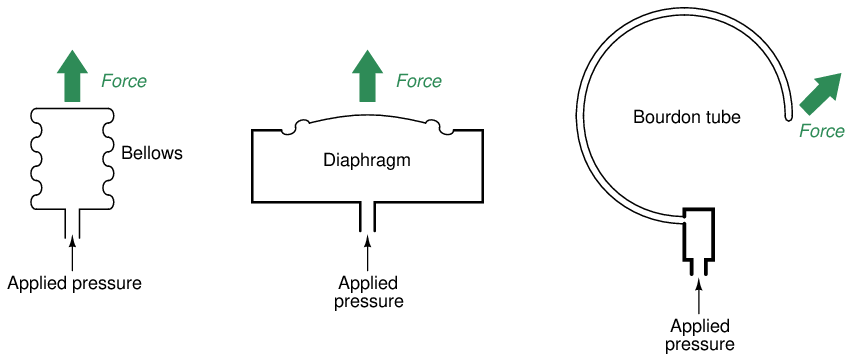

Mechanical pressure-sensing elements include the bellows, the diaphragm, and the bourdon tube. Each of these devices converts a fluid pressure into a force. If unrestrained, the natural elastic properties of the element will produce a motion proportional to the applied pressure.

Bellows resemble an accordion constructed from metal instead of fabric. Increasing pressure inside a bellows unit causes it to elongate. A photograph of a bellows is shown here:

A diaphragm is nothing more than a thin disk of material which bows outward under the influence of a fluid pressure. Many diaphragms are constructed from metal, which gives them spring-like qualities. Some diaphragms are intentionally constructed out of materials with little strength, such that there is negligible spring effect. These are called slack diaphragms, and they are used in conjunction with external mechanisms (e.g. springs) producing the necessary restraining force to prevent damage from applied pressure.

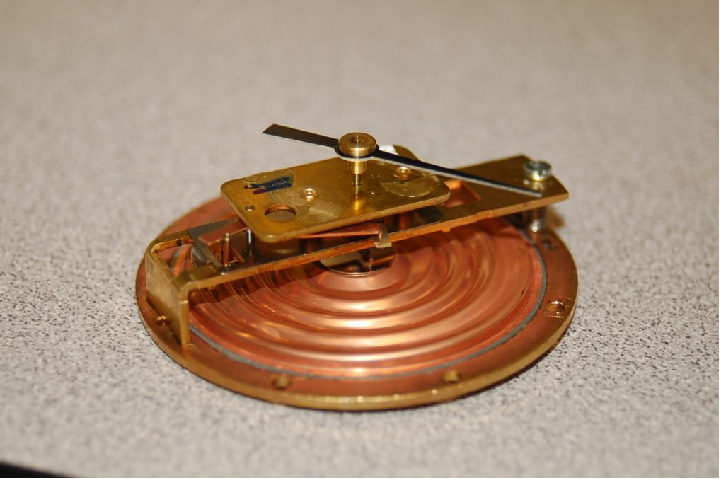

The following photograph shows the mechanism of a small pressure gauge using a brass diaphragm as the sensing element:

As pressure is applied to the rear of the diaphragm, it distends upward (away from the table on which it rests as shown in the photograph), causing a small shaft to twist in response. This twisting motion is transferred to a lever which pulls on a tiny link chain wrapped around the pointer shaft, causing it to rotate and move the pointer needle around the gauge scale. Both the needle and scale on this gauge mechanism have been removed for easier viewing of diaphragm and mechanism.

Bourdon tubes are made of spring-like metal alloys bent into a circular shape. Under the influence of internal pressure, a bourdon tube “tries” to straighten out into its original shape before being bent at the time of manufacture.

Most pressure gauges use a bourdon tube as their pressure-sensing element. Most pressure transmitters use a diaphragm as their pressure-sensing element. Bourdon tubes may be made in spiral or helical forms for greater motion (and therefore greater gauge resolution).

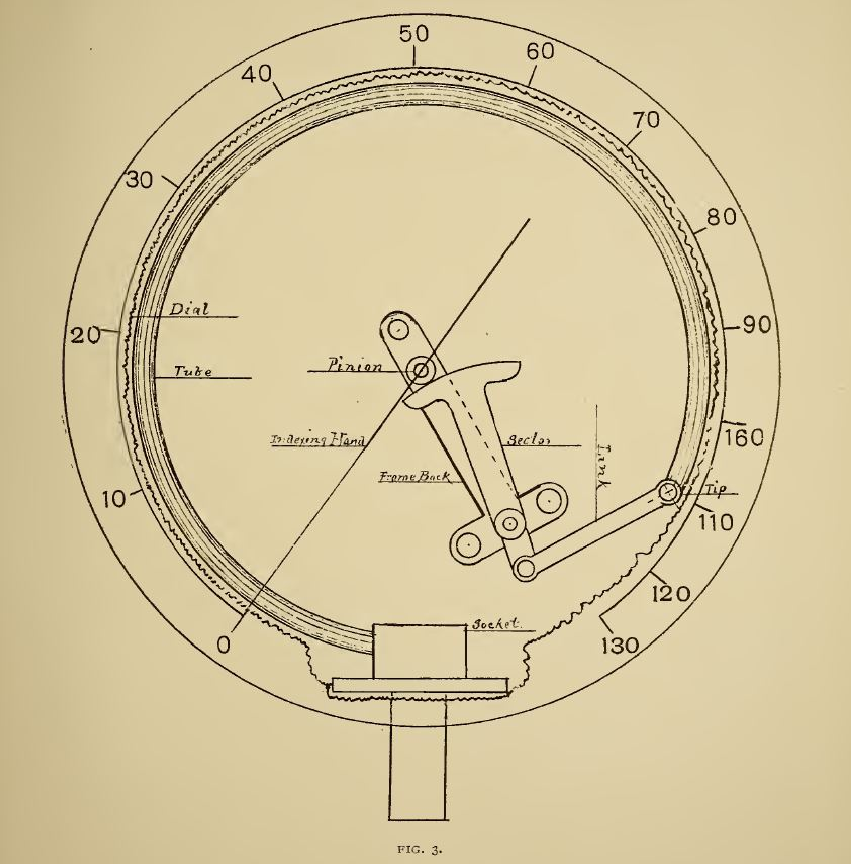

The Bourdon tube pressure element is a very robust and time-tested design. An illustration taken from page 471 of volume 1 of Cassier’s Magazine published in the year 1891 shows a typical C-shaped bourdon tube pressure gauge mechanism complete with gears and pointing needle:

Looking closely at the labeled components of this mechanism, we see a circular “pinion” touching a curved “sector”. Both of these are gears meshing with one another, but as is typical with mechanical drawings the individual teeth of the meshing gears are not shown.

It is a useful mental exercise to imagine the components of this gauge moving under the influence of a rising fluid pressure. The bourdon tube will straighten, resulting in its tip extending outward from center (up and right) as its socket remains stationary (anchored to the gauge body). This pulls on the link, which in turn causes the sector gear to rotate counter-clockwise on its bearing axis (that axis anchored on the backing plate of the gauge). This causes the pinion gear to rotate clockwise, driving the needle (the “indexing hand”) clockwise as well, so that the needle’s tip rises up the numerical scale printed on the gauge face.

A photograph of a C-tube pressure gauge mechanism (taken from the rear of the gauge, behind the pointer and scale) reveals its mechanical workings:

The dark, C-shaped tube is the bourdon tube sensing element, while the shiny metal parts are the linkage, lever, and gear assembly.

The next photograph shows a spiral bourdon tube, designed to produce a wider range of motion than a C-tube bourdon:

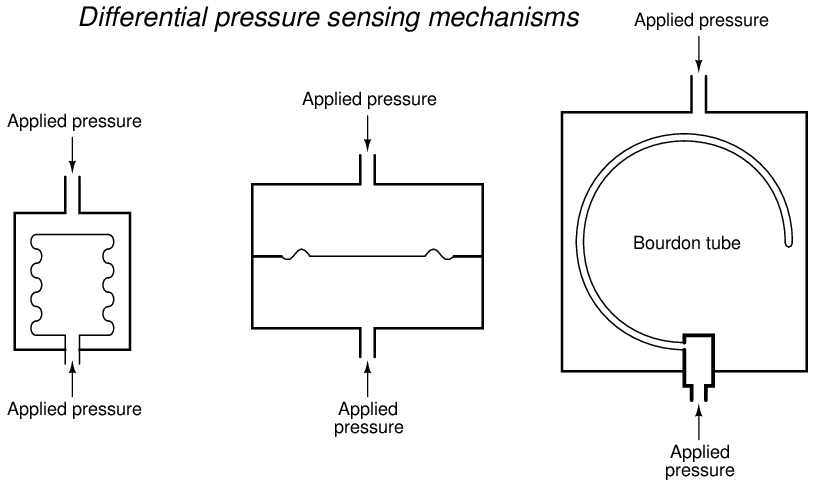

It should be noted that bellows, diaphragms, and bourdon tubes alike may all be used to measure differential and/or absolute pressure in addition to gauge pressure. All that is needed for these other functionalities is to subject the other side of each pressure-sensing element to either another applied pressure (in the case of differential measurement) or to a vacuum chamber (in the case of absolute pressure measurement).

This next set of illustrations shows how bellows, diaphragms, and bourdon tubes may be used as differential pressure-sensing elements:

The challenge in doing this, of course, is how to extract the mechanical motion of the pressure-sensing element to an external mechanism (such as a pointer) while maintaining a good pressure seal. In gauge pressure mechanisms, this is no problem because one side of the pressure-sensing element must be exposed to atmospheric pressure anyway, and so that side is always available for mechanical connection.

A differential pressure gauge is shown in the next photograph. The two pressure ports are clearly evident on either side of the gauge: