A positive displacement flowmeter is a cyclic mechanism built to pass a fixed volume of fluid through with every cycle. Every cycle of the meter’s mechanism displaces a precisely defined (“positive”) quantity of fluid, so that a count of the number of mechanism cycles yields a precise quantity for the total fluid volume passed through the flowmeter. Many positive displacement flowmeters are rotary in nature, meaning each shaft revolution represents a certain volume of fluid has passed through the meter. Some positive displacement flowmeters use pistons, bellows, or expandable bags working on an alternating fill/dump cycle to measure discrete fluid quantities.

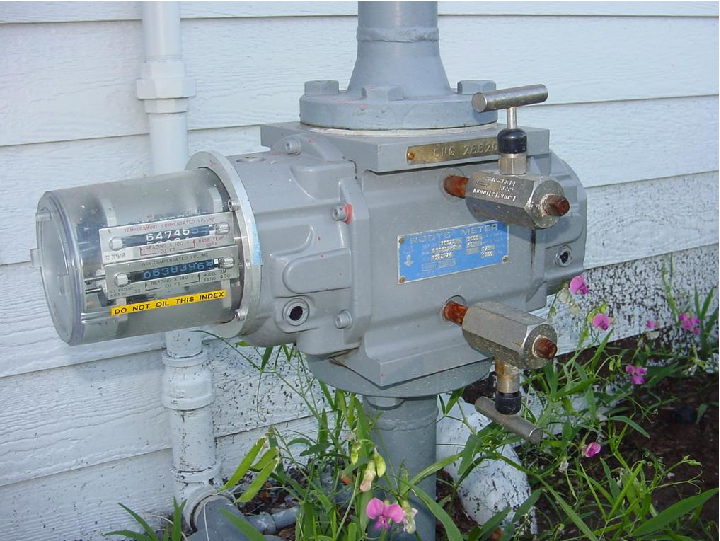

Positive displacement flowmeters have been the traditional choice for residential and commercial natural gas flow and water flow measurement in the United States (a simple application of custody transfer flow measurement, where the fluid being measured is a commodity bought and sold). The cyclic nature of a positive displacement meter lends itself well to total gas quantity measurement (and not just flow rate), as the mechanism may be coupled to a mechanical counter which is read by utility personnel on a monthly basis. A rotary gas flowmeter is shown in the following photograph. Note the odometer-style numerical display on the left-hand end of the meter, totalizing gas usage over time:

Positive displacement flowmeters rely on moving parts to shuttle quantities of fluid through them, and these moving parts must effectively seal against each other to prevent leakage past the mechanism (which will result in the instrument indicating less fluid passing through than there actually is). In fact, the defining characteristic of any positive displacement device is that fluid cannot move through without actuating the mechanism, and that the mechanism cannot move without fluid passing through. This stands in contrast to machines such as centrifugal pumps and turbines, where it is possible for the moving part (the impeller or turbine wheel) to jam in place and still have fluid pass through the mechanism. If a positive displacement mechanism jams, fluid flow absolutely halts.

The finely-machined mechanical components of a positive displacement flowmeter will suffer damage from grit or other abrasive materials present in the fluid, which means these flowmeters are applicable only to clean fluid flowstreams. Even with clean fluid flowing through, the sealing surfaces of the mechanisms are subject to wear and accumulating inaccuracies over time. However, there is really nothing more definitive for measuring volumetric flow rate than an instrument built to measure individual volumes of fluid with each mechanical cycle. As one might guess, these instruments are completely immune to swirl and other large-scale fluid turbulence, and may be installed nearly anywhere in a piping system (i.e. no need for long sections of straight-length pipe upstream or downstream). So long as the fluid is clean, high viscosity poses no problem for a positive displacement flowmeter, which makes them well-suited to the measurement of such fluids as syrups, gels, and heavy oils. Positive displacement flowmeters are also very linear, since mechanism cycles are directly proportional to fluid volume.

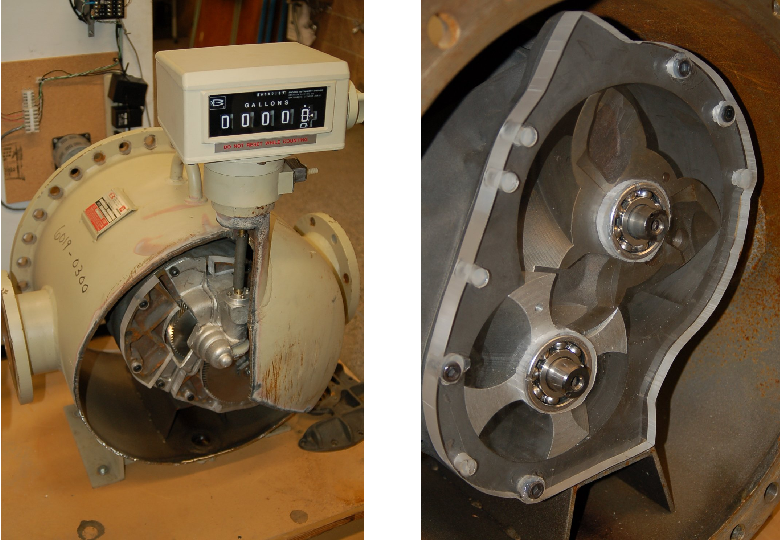

A large positive displacement flowmeter used to measure the flow of liquid (registering total accumulated volume in units of gallons) is shown here, having been cut away for use as an instructional display:

The left-hand photograph shows the gear mechanism used to convert rotor motion into a visible total readout. The right-hand photograph shows a close-up of the interlocking rotors (one with three lobes, the other with four slots which those lobes mesh with). Both the lobes and slots are spiral-shaped, such that fluid passing along the spiral pathways must “push” the lobes out of the slots and cause the rotors to rotate. So long as there is no leakage between rotor lobes and slots, rotor turns will have a precise relationship to fluid volume passed through the flowmeter.